Some background first: the Minoan eruption at around 1613 BC

Ruins of the Minoan city buried on Santorini near the village of Akrotiri

The famous ship fresco - a wall painting from the Minoan city possibly representing the island with its caldera at the time before the eruption.

The present-day caldera of Santorini with the white Minoan deposit visible as the thick topmost layer in the cliffs.

The Minoan pumice layer in the quarry near Fira.

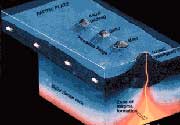

, the eruption began with a heavy rain of hot pumice falling out from the eruption column that reached about 40 km height. The pumice fall-out from the first phase of the eruption blanketed the whole of the island, the surrounding sea and islands to the east of Santorini. In some places, the pumice layer deposited was more than 7 meters in thickness.

The importance of a precise date of the Minoan eruption is given by mainly two factors: the deposit of the eruption is very widespread in the whole region of the Eastern Mediterranean and even beyond, and it can thus be used as a time marker: everything beneath is older, everything above it is younger. The second fact is that it happened during an epoch in Early history that attracts great interest among historians for various reasons: the era of decline of the Minoan civilization, where wide-spread effects of the eruption (such as disruption of regional trade lines, tsunami damage, climatic perturbations in years following the eruption) might play a significant role, a mysterious period of foreign leadership in Egypt, possible connections to many ancient myths and stories from many cultures including biblical references and so on.

Before the eruption, the island was host to a sophisticated and rich, seafaring and trading society who was related to the Minoans on Crete. Their city was totally buried under many meters of volcanic ash.

The so-called Minoan eruption can be compared to, but was much stronger stronger than the famous

"Plinian" eruption at Vesuvius volcano in Italy, which happened almost 2000 years later, in the year 79 A.D. near Pompeii - the famous Roman city buried under the pumice of Vesuvius. The Ancient Minoan city excavated near the village of Akrotiri on Santorini is therefores often called the

"Pompeii of the Bronze Age", to stress the similarity to Pompeii and its importance for prehistoric archaeology. One of the most notable findings were a large number of

vivid wall frescoes showing life in the town at around 1600 B.C.

Virtually all vegetation and wood present in man-built structures seems to have been burnt,- despite intense geological, archaeological research, excavations and mining on the island for about 200 years, no significant amounts of preserved wood, organic material or charcoal from the time of the eruption have been recovered (although once found and tragically lost, but this is another story,- read Walter's book...!) Unfortunately, because it would have provided geologists and archaeologist with a means to determine the precise age of the eruption using the

C-14 radiocarbon method.

Discovering the site (Nov 2002)

The caldera cliffs near the site looking north; the Minoan deposit is the thick topmost layer including a 5 m thick base of fall-out pumice. Construction is consuming the pumice layer from top down, and destroying important geological features visible in the wall.

The caldera cliffs near the site looking south.

The first photo of the site: holes in the basal pumice layer, here about 5 meters thick, where the branches of the tree were. The "Science" branch was from the large hole. A piece of wood is lying on the ground...

Other holes left of the one where the "Science" branch was from; they have been covered now (in 2007) by continuing careless building activity.

Near the site is a man-made structure resembling a wall or well; perhaps the spot had a particular significance due to the presence of rare trees, as today, 4000 years ago. (my fieldbook for scale)

Two large, connected holes at the base of the pumce. Deep inside one of them, one could barely see wood, too. This piece was first recovered in July 2007 and brought a wonderful, almost 2 meter long branch back to light, which is now displayed in the new geological museum in Perissa.

The cross section of the branch visible in the large hole at about 2 meters height in the wall; this is the piece that was first recovered and subject of the published investigation.

Walter Friedrich at the site (Feb. 2003)

I found the site in late 2002, when I was doing field work on Santorini

searching for clues about the shape of the island and its caldera

before the eruption. It is located in the upper caldera cliffs near Athinios harbour. When I found a way to reach the base of the pumice at a spot where construction of a new building had opened an access route into the cliff below, I wandered along the base of the Minoan pumice which forms a narrow ledge in most places and allows to inspect it for several hundred meters in this area. Going south, I first noticed a number of larger and smaller round holed in the first layer of pumice. Immediately I thought about a tree that once must have stood here, but didn't hope much to find charcoal or other remnants - so far, virtually none had been found anywhere during many decades of research.

The bigger my

surprise and joy, when I came closer: one of the first things I noticed was a dark piece of wood

lying on the ground beneath one of the larger holes. It was a 40 cm long, 5 cm thick piece of an olive tree branch, partly charred on the outside, but essentially, it was still intact wood! Around on the ground were many smaller pieces of wood and black charcoal... This alone would not have meant necessarily it came from the tree holes and was 4000 years old, but I lcould peer into one of the larger holes about 2 meters above this spot and one could see a

whole cross section of a thick branch!

I knew this was a major discovery, which felt as if I had struck a gold mine and somehow unreal. It took some time to get used to it and really believe it. Another, even larger hole, as wide as a man and nearer to the ground, was located about 7 meters right of the first cluster of holes and belonged to another tree. It was empty in the lower accessible areas. Its hollow shape was gently curved and let easily imagine the trunk or a major branch that was itself branching into two parts. Far inside to the above of the larger hole, I could barely see something dark, what must be more charcoal or wood...

(eventually, this was recovered in 2007 and provided a wonderful 2 meter long piece of a branch now displayed in the new geological museum in Perissa.)

There was little I could do immediately, and I left only with some wood sampled from what had fallen out from the holes and was simply sitting on the ground.

Recovering the branch of the olive tree (May 2003)

When I talked with archaeologists working at the excavation site of Akrotiri, I met very little interest! I decided to show it to ome of them (who turned out to suffer vertigo at the spot and was only happy to get back alive...). Unfortunately, I was then told that the site was not important enough and besides that, impossible to protect. There was no a comment on the possibility to have

not only many kilograms of WOOD, but

intact tree rings etc. from the eruption!

I informed professor Walter Friedrich who came as soon as he could free himself from teaching and we visited the site again in February 2003. Given the negative reaction from Akrotiri, we agreed it was best to try to recover wood on ourselves to investigate it ourselves.

The opportunity arose when was guiding a group for the tour

Fascination Volcano in May 2003. One of the participants was Peter, a Dutch geologist. Peter agreed to help me to try to recover the branch whose cross section one could easily see in the larger hole about 2 meters above ground; it looked as if one might be able to simply pull it out... But how wrong!

It turned out difficult enough: the site was (is) only accessible on a narrow ledge on the steep caldera wall, 200 m above the water, and below a 30 m vertical cliff of pumice and ash, with large blocks in the loose deposit. Bringing a ladder seemed too difficult and risky, so we decided we would try it by standing on each oach other's shoulder. In fact, this worked well. Peter climbed on my shoulder, so his own shoulder was at the height of the hole and he could begin digging away the pumice around the piece of wood, which was falling around me.

Trying to simply pull out the branch didn't work. Peter dug pumice away around the branch as much as he could reach, which took a while. Finally, we realized that the branch was curved and still stuck deep inside, refusing to get loose. We simply had to move the branch itself, even risking to break it and only recover a part. The risk that the site would be destroyed within one season - there's construction of a new hotel going on in the pumice wall above the site.

It took us almost two hours carefully moving the branch up and down, left and right, making it loose slowly from its surroundings, until Peter finally could pull it out: it was around 10 kg heavy, about 1 meter long and 15-20 cm in diameter. In perfect condition, it was only charred on the outside where the bark was still visible, and my greatest fear was it might be used as firewood if someone local got hands of it. However, I had to leave it on the island, for sure.

From Santorini to Heidelberg (2003-04)

I left the branch with friends on Santorini whom I could trust they would not burn it. During the summer months of 2003, Walter managed to built a team of scientists and specialists who were to analyze the wood. The branch thus travelled to Athens, then to Arhus and finally to Heidelberg, where the analysis were made that were eventually published presented in the Science paper. This part of the story is found in numereous places elsewhere.

Destruction of the site (ongoing)

Debris of loose deposit is being dumped from the construction site in 20 meter above the site. The first hole where the "Science" branch was recovered is now accessible by foot and will soon be covered.

View inside the hole, were the continuation of the original branch is still visible (now recovered and destined for the museum in Perissa)

Organic remnants of olive leaves in the basal layer of the pumice, proof that the tree was alive at the time of the eruption.

The site and the second branch.

Sample of ash with olive leaves.

The second piece of wood from the same hole after its recovery.

Numerous pottery fragments are found in the Minoan soil near the site

Walter Friedrich on his way from the site

The sad news is that the site is being destroyed quickly: construction in the pumice layer above is ongoing, dumping debris onto the narrow ledge at the site. Drainwater is diverted into the old gully next to the site, which increased local erosion.

In 2007, the hole of the original piece of branch was almost covered by debris already. In a sense, this was an advantage, too, as it allowed me to recover another piece of the same branch as the one from the "Science" story (see photos); it had been just deeper inside the hole, but now I could simply creep into the hole and dig myself towards the branch piece...

Later, in July 2007, a group of 4, with more adequate equipment, managed to recover the third larger piece, a beautiful, 2 meter long part of a branch from the second tree to whom the larger holes just right of the original site belonged. This piece is now in the new geological museum of Perissa; the other one shown here is still with friends on the island, but it's planned to give it to the the museum as well.

In late 2007, only about half of the site is still intact and it is foreseable that within a few years at most, all evidence

in situ will be gone.